All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Unmasking Stigma: A Qualitative Exploration of Nurses in Urban and Rural Indonesia during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

Background

Studies investigating the manifestations of stigma on nurses during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia are still limited. Moreover, previous studies have primarily focused on nurses directly involved in COVID-19 care.

Objective

This study aims to thoroughly explore the sources of stigma and the spectrum of stigma manifestations—enacted, anticipated, and internalized—experienced by Indonesian nurses working across different levels of healthcare in the urban and rural settings of Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative descriptive study using semistructured interviews was conducted. Thirty-three nurses who worked in the urban area of Jakarta and in rural areas of West Kalimantan participated. Data analysis was carried out using the framework method.

Results

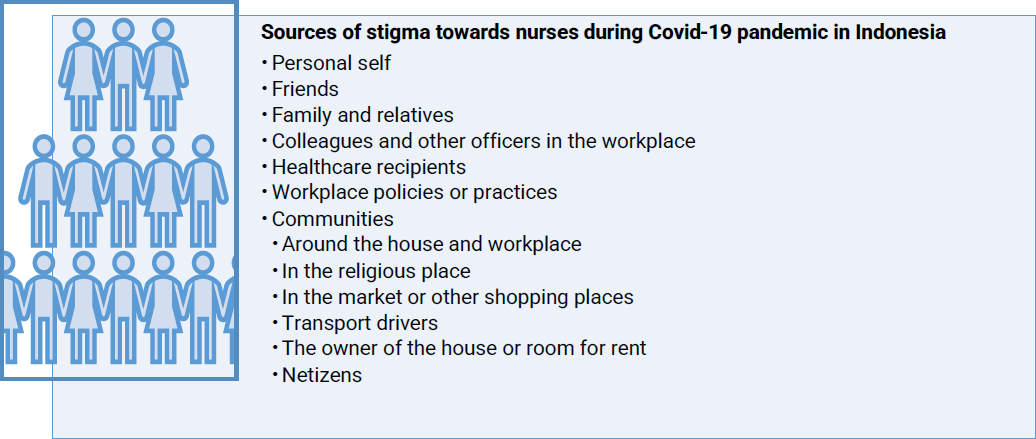

The findings showed that Indonesian nurses, regardless of their context (i.e., place of stay, COVID-19 status, level of health service, or area of service), encountered stigma during the pandemic. Sources of stigma varied widely and included self-stigma, stigma from family members, friends, health care recipients whether in hospital or out of hospital, colleagues, and other staff in the workplace, workplace policy and practices, the community surrounding their homes, markets, transport drivers, room rental owners, religious community, and online communities (netizens). Nine forms of enacted stigma, two forms of anticipated stigma, and four manifestations of internalized stigma were identified.

Conclusion

Not only do nurses bear the stigma related to the COVID-19 threat, but nurses also endured and felt stigma related to their nursing profession and the stigma associated with mental health issues. Indonesian nurses faced a triple burden of stigma during a pandemic, such as COVID-19, as stigma perpetuated from multiple levels of sources and intersected with other issues beyond the threat of the virus itself. To enhance nurses' resilience in future health crises, greater efforts are required to mitigate stigmatization against them.

1. INTRODUCTION

Stigma is generally understood as a negative and often unfair belief toward something or someone, usually associated with unideal conditions. In the context of a disease, such as HIV/AIDS, TBC, leprosy, or even mental health, stigma is commonly found. The COVID-19 pandemic, declared by the World Health Organization [1] started on 11 March 2020, has added to the history of stigma globally. During this time, many individuals experienced stigmatization, leading to physical and psychological harm, which significantly impacted their well-being [2]. Stigma has been considered as a hidden threat of the COVID-19 disease [3], affecting not only ordinary people but also professionals, especially healthcare workers [4-6]. Healthcare workers who directly provided care for COVID-19 patients [7], as well as those who were not involved in treating COVID-19 patients, both experienced stigma [8].

Among healthcare professionals, nurses were significantly impacted by stigma [9]. Despite their enormous contribution to society, during the pandemic, nurses had more potential to be stigmatized. Research highlighted that nurses experienced stigma from different sources [10]. A phenomenology study of 19 Italian nurses showed that they experienced stigma in their working environment and family [9]. A study among nurses working in isolation and quarantine facilities in New Zealand revealed that nurses are considered more as a source of transmission rather than inhibiting transmission to society [11]. In Indonesia, according to several studies, nurses were experiencing stigma during the pandemic as well [12-20]. A study at the beginning of COVID-19 pandemic revealed that nearly 50% out of 509 nurses around Indonesia felt they were being stigmatized [14]. Many nurses also felt negative about their self-image [21]. Compared with doctors, the odds of nurses receiving stigma were much higher [20]. The prominent effect of stigma on nurses was on their mental well-being [22]. Studies in Korea and Egypt showed that nurses experienced stress and depression [23, 24]. A study in Saudi Arabia indicated that nurses also suffered from frustration and anxiety [25]. In Indonesia, stigma was also associated with the occurrences of anxiety, fear, depression, and mental health crises [12]. High levels of stigmatization also significantly lowered nurses’ resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic [18].

Despite stigma being a critical issue, there is still a lack of studies that thoroughly examined stigma manifestations among Indonesian nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most of the approaches used were quantitative designs, focusing primarily on the general magnitude of stigma in terms of numeric proportions [12, 17, 18, 20, 21]. In the studies that aimed to understand stigma manifestations, the focus was predominantly on experienced stigma, without a clear distinction between experienced, perceived, and internalized stigma [19, 26]. Additionally, these qualitative studies typically included only nurses working in hospital settings and directly treating COVID-19 patients [19, 26]. A significant gap exists in exploring a broader range of stigma manifestations among nurses in both hospital and non-hospital settings in Indonesia during the pandemic. Research is needed that would study the stigma experienced by nurses, regardless of whether they were involved in direct COVID-19 patient care. Moreover, a comprehensive approach should consider all levels of healthcare services and encompass various locations, allowing for a deeper understanding of stigma in different contexts. The aim of this study is to address these gaps by thoroughly examining the sources and manifestations of stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic among nurses in Indonesia. This includes those working in primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare levels from both rural and urban settings. By broadening its scope, we aim to provide a more comprehensive perspective on the experiences of Indonesian nurses during this challenging time. We hope this study will also serve as a foundation for developing more nurse-friendly policies and practices for future crises.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This research is a part of the research project entitled “Exploration of stigma towards nurses in Indonesia during COVID-19 pandemic”. This study used a qualitative descriptive approach with semistructured interviews to describe the types and sources of stigma encountered by participants. Qualitative descriptive research is used to gain a straightforward and comprehensive description of experiences that are close to the data [27-29].

2.2. Stigma Concept

The conceptualization of stigma in this study used the concept of enduring stigma from Weiss’ Extended Scambler’s Hidden Distress Model [30]. According to this, stigma can be categorized into two forms: enduring stigma and perpetrating stigma. Enduring stigma is a type of stigma experienced and felt by the stigmatized group that can be distinguished into enacted, anticipated, and internalized stigma. Enacted stigma or experienced stigma is a discriminatory treatment received either directly or indirectly from other people; anticipated stigma or perceived stigma is the perception of the possibility of negative or unfair treatment from others; whereas internalized stigma or self-stigma is a discredited view of oneself from others that has been adopted and accepted so that a person with certain conditions begins to stigmatize himself [30].

2.3. Study Setting

Jakarta province and the rural area in West Borneo province were selected as the areas of research. Jakarta was selected to represent urban cases and West Borneo to provide data from rural areas. These provinces were selected after consideration that 100% area in Jakarta was categorized to be urban and 84.9% of the West Borneo area was categorized to be rural area, according to the government’s data [31, 32]. Based on this fact, researchers believed that the findings from these two different areas could help to depict the national condition. Since the findings were derived from two contexts, both urban and rural, this would also enable triangulation of data [33].

2.4. Sampling and Selection

Purposive sampling was used. The participants in this study were Indonesian registered nurses who were actively working in healthcare facilities and had experienced stigmatizing behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurses who worked in mental health facilities or did not work directly with patients and community members, such as for administrative issues, were excluded from the study. Recruitment was carried out by posting regular announcements on social media or sending emails to various institutions, such as hospitals, faith-based organizations, or educational institutions in the targeted area. An electronic poster was used. Interested individuals were provided with a questionnaire to fill out. The list of potential participants from the questionnaire was then reviewed and purposively selected based on the aforementioned inclusion characteristics. The details about what was asked in the questionnaire were elaborated on in the data collection section.

In the next step, prospective participants were contacted and provided with detailed information about the research, a link to an online platform to access the informed consent form, and to select an interview schedule that fits the potential participant. Participants were given a flexible time to decide on their participation. This was given in consideration of the high load of work they might have had at the time of the pandemic. One out of 34 nurses who had agreed to participate withdrew due to time constraints. A small number of participants knew one of the authors (ER) due to past work experience and the status of former students.

Recruitment began in October 2021 (20 months after the pandemic started) and ended in the initial week of January 2022. Participant recruitment was discontinued once the theoretical saturation level reached. Several ways were addressed to determine whether the saturation point had been achieved. First, the transcription process was conducted as soon as possible after the interview using a designated template. After each transcription process was done, researchers read the transcription and recorded the findings in an Excel matrix that was accessible to all team members. The findings were added under a designated column that corresponds to the study objectives: the source of stigma, experienced, anticipated, and internalized stigma. Regular sharing sessions were also held to facilitate the decision.

2.5. Data Collection

Data from participants were collected from the questionnaire that was given in the recruitment process as well as from the interview process of each participant.

From the online questionnaire, information about age, gender, marital status, religion, ethnicity, education status, domicile, type of residence, type and unit of the workplace, information, whether the participant has ever been directly involved in COVID-19 health services, location (city or district) of the health facility in the provinces where they work, length of work, and whether or not they have experienced stigmatizing behaviors during pandemic. For the last question, to avoid misinterpretation and unfamiliarity with the word “stigmatizing behavior,” the phrase “felt and experienced to be treated differently” was used in question.

To understand the variety of stigma experiences of nurses currently working in a pandemic situation, semistructured interviews were conducted using a guide that has been tested on two nurses from each region (Jakarta and Rural West Borneo). Online interviews with a virtual meeting platform were used. Consideration of this method was the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that limited the possibility of face-to-face direct interviews and the ability of researchers to interact and be aware of the visual identity and motions of the participants. Moreover, at the time of the research being held, the pandemic situation had pushed more health workers in urban and rural areas to use online meeting tools in order to get a quick update or to access the extensive training on COVID-19 from the government and other parties. This research was conducted almost 2 years after the public health emergency international concern was announced. Therefore, researchers believe that more health workers are already familiar with the online tool.

To build trust and help participants feel confident to talk about the issue, the online interviews were designed with a single participant and interviewer in a trusted environment where only the interviewer and participant were in the online room. The surrounding physical area of the interviewers was also ensured to be free from people and noise. Moreover, to obtain rapport, the interview was also structured. In the opening part of the interview, an introductory session was held. Questions related to names and daily life activities were asked. Only after this stage, participants were given questions related to the study objectives. The interview was held in an exploratory manner and with field notes. Three researchers, consisting of two females (YM, ER) and one male (FS), conducted the interviews. All researchers were trained in conducting qualitative approaches and had produced several qualitative research reports. To avoid biases, preconception regarding stigma was attempted to be removed during the interview. This is important, considering all three interviewers have health backgrounds, from public health, nursing, and health management.

In total, 33 nurses were interviewed. The interview total time was 1951 minutes, with an average of 60 minutes for every participant. Following the interviews, compensation for internet quotas in a reasonable amount (IDR 100.000) was given to the participants. All recordings were then stored in a drive that could only be accessed by researchers.

2.6. Data Analysis

The framework method [34, 35] was used in the analysis process to generate themes. This analysis involved seven stages: transcription process, familiari- zation with the interview, coding, developing a working analytical framework (thematic framework), applying the analytical framework, charting data into the framework matrix, and interpreting the data. This method was chosen because it could help the researchers obtain a holistic overview from an extensive data set in a structured manner [34].

The first stage in the analysis was the transcription process. The recordings were transcribed immediately after each interview was done. Three nursing students who have been trained with transcribing skills were helping with this process. A similar Microsoft Word format was used for all transcripts. Each time a transcript was ready, it was sent to the participants to be validated first through a member-checking process. All participants reread the transcripts and were allowed to add or revise the information. The transcript then would be corrected according to the input received, if any. To maintain understanding, the member-checking process was led by each researcher, who became the interviewer for each participant. Further steps of analysis only began after approval of the transcripts had been obtained from the participants.

The final transcripts were then reread to help the researchers re-familiarize themselves with the infor- mation. In the next stage, six transcripts were carefully selected to build the initial themes known as the analytical or thematic framework. The selection was made based on the representativeness of diverse backgrounds of participants from both the urban and rural sides of provinces. During the coding and categorizing process, Weiss’ Extended Scrambler’s Hidden Stress Model [30] was the point of reference in the process to indicate the enacted, anticipated, and internalized stigma. The framework built could then be applied to the whole dataset. The final analytical framework was completed after all transcripts had been coded (YM, ER, FS) [34]. At the next stage, a matrix was generated and the data was charted to help compare the data of participants and within each category. In the final step, an interpretation memo was developed to structure the findings. The process was time-consuming, and it was done without the help of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) due to financial limitations. Pen, paper, and Microsoft Excel were used to search for themes, clusters, and patterns.

2.7. Rigor and Trustworthiness

Several measures were taken to enhance the rigor and trustworthiness of this study. The findings were obtained from participants with a diverse range of backgrounds and settings, which contributed to greater validity and provided a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. The research team maintained a reflective approach, considering individual positions and educational backgrounds in public health, nursing, medicine and healthcare management, to improve the validity and integrity of the data while minimizing potential biases. This approach was applied throughout both the data collection and data processing phases. Private online meeting rooms were used for interviews, with only the interviewer present. This setup fostered trust and rapport, allowing for deeper exploration with participants. During data processing, all transcripts underwent member-checking to ensure accuracy before analysis. Regular meetings among the research team were held to discuss findings and ensure consistency. The researchers also maintained a strict ethical commitment to participants by following principles such as do no harm, privacy, anonymity, confidentiality, and obtaining informed consent. COREQ's standards were used to guide the reporting of research findings.

| Characteristics | n | % | X̄ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Gender Female Male |

25 8 |

76 24 |

- |

|

Age (years) <31 31+ |

16 17 |

48.5 51.5 |

32.27 |

|

Marital Status Single Married |

15 18 |

45.5 54.5 |

- |

|

Education qualification in nursing Diploma III (Vocational) Bachelor Magister |

16 16 1 |

48.5 48.5 0.03 |

- |

|

Service coverage Urban (Jakarta) Rural (West Borneo) |

16 17 |

48.5 51.5 |

- |

|

Type of healthcare facility Secondary/Tertiary Primary |

24 9 |

72.7 27 |

- |

|

Experience as nurse (year) <8 8+ |

16 17 |

48.5 51.5 |

9.17 |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of Participants

Thirty-three (33) nurses with an average age of 32 years were involved in this study. Most participants were female (n=25; 76%) and worked at the secondary and tertiary healthcare levels (n=24; 73%). More information can be seen in Table 1.

3.2. The Stigmatized

From the findings, it could be concluded that stigma was experienced by nurses in various contexts during the pandemic. It was experienced in urban and rural areas (place of stay), in different levels of health services. Stigma was also experienced by participants with different COVID-19 statuses; those who contracted with COVID-19, have survived COVID-9, or have not contracted with COVID-19 were impacted. Stigma occurred even when the participants had diligently taken safety protocols such as using personal protective equipment, taking a shower after working in COVID-19 area, or undergoing routine swab testing. In terms of area of service, stigma was experienced not only among participants who dealt with COVID-19 patients in hospitals but also among those who worked in the community field for COVID-19 or other purposes outside COVID-19. Moreover, participants who were not directly handling COVID-19 management—for example, participants who were working at the green zones (i.e., COVID-19 free zones) in the hospital-experienced stigma behavior as well.

3.3. The Sources of Stigma

Stigma against nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic was perpetuated through various channels (Fig. 1). Nurses themselves were the source of stigma. Other than that, friends and family members were the closest domains to nurses from which stigma was felt. Family members included both the nuclear and extended family of participants. In healthcare facilities where nurses work, participants received various types of stigma from other co-workers, including nurses, pharmacists, and other officers, as well as from healthcare beneficiaries such as patients and their families who accompanied them. Community members whose homes nurses visited for COVID-19 purposes, such as disease testing, tracing, and treatment, and for other objectives not related to COVID-19 control (e.g., routine health checks) also stigmatized nurses. In addition, nurses also receive stigma from workplace policies or practices. Nurses also felt stigmatized by the community at large, including those in surrounding neighborhoods, the community around the hospital, passengers in public transportation, drivers of transportation apps, pedestrians, residents in remote areas, owners of rental rooms (named kos-kosan in Indonesia), sellers at kiosk or small shop (known as warung in Indonesia), place of worship, and even from netizens.

3.4. The Manifestations

Stigma manifestations toward nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic were categorized under three categories. First, stigma forms that are related to the perceived COVID-19 threat. Second, forms of stigma that are related to the disliked or unfavorable characteristics in the nurse profession. And thirdly, stigma is associated with mental health (Table 2).

Below, the manifestations are elaborated. Quotes (Qn) are provided and can be seen in Table 3.

Sources of stigma towards nurses during COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia.

Table 2.

| Stigma Manifestations | Stigma Category* |

|---|---|

| Enacted Stigma | - |

| Physical avoidance | C |

| Limited personal space and autonomy | C |

| Suspicious behaviors | C |

| Rejection | C |

| Accusing and demeaning words | C, NP |

| Unusual stare | C |

| An exclamation that felt isolating | C |

| Unequal treatment compared to doctors | NP |

| Unfair treatment of family members of nurses | C |

| Anticipated stigma | |

| Fear of being stigmatized while on duty and out of duty | C |

| Fear of receiving stigma due to seeking psychological support | MH |

| Internalized stigma | |

| Viewing self as a carrier of the COVID-19 virus | C |

| Having a low impression of self and job | NP |

| Feeling like the constant object of attention | C |

| Allowing discriminatory treatment of others | C |

| Stigma Manifestations | Stigma Category* | Source of Stigma | Example of Statements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enacted Stigma | |||

| Physical avoidance | C | Communities | Q1: “As a healthcare worker, for example, we went to shopping places or other places at which they already knew we were health workers. Yeah, we were shunned by people who knew us.” (P32, Rural) Q2: “We were shunned. Seemed like they did not want to take the money.” (P17, Rural) Q3: “It was more about the neighbors. They avoid me because they were afraid” (P1, Urban) |

| Family and relatives | Q4: “My family is still the same until now, still keeping the health protocol very strict. Whenever I want to go home, I must first take PCR and quarantine myself for days.” (P6, Urban) Q5: “At that time, the behavior was different to me compared to my other family when we were sick. The difference was that if other family members were sick, they still visited them by wearing a mask. Meanwhile, when I was sick, I had to be alone. I took my food alone. Went to the bathroom back and forth by myself. So, I really felt alone.” (P26, Rural) |

||

| Colleagues or other officers in the workplace | Q6: “Sometimes if we meet in an elevator, (she/he) immediately takes a distance.” (P10, Urban) Q7: “When a patient who was originally in the green zone had indications of having Covid, they [nurse co-workers] have to report to us in the red zone. So, we’re waiting for them to report but they didn’t come. It turned out they were still telling each other like “Go ahead, you report it!” Like that.” (P2, Urban) Q8: “The pharmacy is even crazier. So, before Covid, they usually delivered the medicine to our room by a transporter officer. Now, since Covid, we are the ones who are told to pick it up and the medicine is put on the side of the road in our corridor. They don’t want to contact us. They just said “Sis, the medicine is at the crossroads, please take it.” (P7, Urban) |

||

| Limited personal space and autonomy | C | Family and relatives | Q9: “In the first month, my bedroom was separated from the others. I was also separated when eating.” (P2, Urban) |

| Communities | Q10: “No one was allowed to pass in front of our house in our alley. To that extent.” (P33, Urban) | ||

| Workplace policy practice | Q11: “But while we were [staying in a designated residence for health workers], we weren't allowed to go out, we weren't allowed to leave the room […]. We were controlled and couldn't go out. I didn't go anywhere for 5 months.” (P31, Rural) | ||

| Suspicious behaviours | C | Healthcare recipients | Q12: “They knew that I was a medical worker or nurse. So, I immediately felt like I was being interrogated, “Mrs. [X], do you work for COVID?” like that.” (P10, Urban) |

| Colleagues and other officers in the workplace | Q13: “If we walk in an area called a green zone, or the clean area, we feel uncomfortable when we are detained by security for passing there. Or, when we walk, the way that we pass is cleaned [...]. It seems that we are seen as dirty. We just pass it, then it is cleaned.” (P11, Urban) | ||

| Communities | Q14: “There are definitely some from neighbors, who said something like, ah, nurses like to make people Covid, right? Nurse? They tell lies. In the Javanese term is “Ojo percoyo”” (P21, Rural) | ||

| Friends | Q15: “The most I've ever experienced is, for example, if we're coughing, then they'll immediately be shocked and panic. “What's wrong? How was the swab? Have you had your swab yet?” That's it.” (P15, Urban) | ||

| Rejection | C | Healthcare recipients | Q16: “That time, the cadres and I used to go door to door […] There, they closed the door and the gate.” (P33, Urban) |

| Communities | Q17: “I have been cancelled several times when I ordered drivers online, maybe because they were afraid. Even when I was going from home, I was asked why I was going to the clinic, I said I work there, then my order was cancelled.” (P6, Urban) Q18: “There was someone who said in regard to worship, that person’s family will not come if there are health workers who come to the worship place. I was so sad.” (P2, Urban) |

||

| Accusing and demeaning words (Nurses are seeking financial gain from COVID-19) |

C | Healthcare recipients | Q19: “For me, because I am on the front line, I’m the first to explain it to patients. In my hospital, sometimes, it's not just doctors who explain to patients about being positive for Covid, sometimes we, nurses, also convey the results of antigen tests. So, there we received a lot of stigmas. Well, because of money problems. […] Because of this, people think that we health workers get a lot of money, with the pandemic. So, they say that there are an average number of nurses who will give them Covid status to get money.” (P9, Rural) Q20: “Sometimes I say “We just want to make sure, sir. We do not want to say that you are Covid”. And then, there are words like this, “Yes, then you will Covid us so the funds will come out.” (P16, Rural) |

| Communities | Q21: “So, there is a stigma that we medical workers are making a profit, and there are expressions like “hey, doctors and nurses are on the rise now.” (P6, Urban) | ||

| Accusing and demeaning words (Nurses are carrying the COVID-19 virus) |

C | Communities | Q22: “When I came home, they immediately said, “Here, she is coming home from the Covid unit” like that. “Here, come home with the virus” like that. Lots of stigma from the surrounding environment.” (P15, Urban) Q23: “There were people who responded, “You should stay outside, because you bring the virus to the people at home” like that. (P2, Urban) |

| Family or relatives | Q24: Most of the relatives who found out that we had tested positive as a family, their immediate response was not to think “Oh, that means it's because of [the participant’s name], right? He works at the hospital, right? It was that fast. No one asked what happened first (P2, Urban) | ||

| Accusing and demeaning words (Nurses are not caring and competent) |

NP | Communities | Q25: “People are talking. For example, in social media, people made statuses, for instance, “If you're isolated in a hospital, nurses won’t give you attention. You will only be seen on CCTV. They do not even know if people die. The next thing they know, they're already dead.” (P32, Rural) |

| Accusing and demeaning words (Derogatory nicknames) |

C | Communities | Q26: “Yes, that's Pocong. Pocong rides a motorbike. Pocong walks. During the day, there is a Pocong.” (P33, Urban) Q27: “On social media, there is a comment like this, “If you feel like you are on the front line, you shouldn't be a cry-baby, you are already well paid.” (P8, Urban) Q28: “Well, my nieces, they call me Auntie Corona. Auntie Corona. Like that.” (P11, Urban) |

| Unusual stare | C | Communities | Q29: “They [the community] also saw us differently during a pandemic. They looked very different, even though there was no talk.” (P30, Rural) |

| An exclamation that felt isolating | C | Communities | Q30“Like “Oh, she works at the Community Health Center. Lots of people get Covid. They get this and that. Beware! Not to get too close!”. (P21, Rural) |

| Colleagues and other officers in the workplace | Q31: Well, there are also some friends who seem to give me a bad look. They said, “Don't go near her, she's still Covid”. Even though I was not. “Oh, she's still coughing, don't come near her”, “Don't eat together”. There were things like that.” (P10, Urban) | ||

| Workplace policy practice | Q32: “In a pandemic like that, we already received stigma from our friends. Now, it was added to a hospital announcement like that. I mean, I was not the only one who really felt it. Some seniors also felt like “What the heck! How come we emergency nurses were discriminated against like that!” (P4, Urban) | ||

| Unequal treatment compared to doctors | NP | Healthcare recipients | Q33: “Because families were more aggressive if they were with nurses. Meanwhile, if they were with doctors, they were more accepting.” (P2, Urban) |

| Unfair treatment to family members of nurses | C | Communities | Q34: “My family members went in and out to help with our necessities. When he went out, he passed neighbors’ Tongkrongan [is a term that refers to a gathering place that is used to fill spare time in Indonesian culture]. When my uncle passed by, those who were not wearing a mask when talking to each other, suddenly wore a mask. And they were not greeting my uncle. In fact, my uncle’s COVID-19 results were negative […] but the people who met my uncle did like that.” (P33, Urban) Q35: “There was a family of mine who wanted to shop at the stall and they were not accepted. They were not allowed to leave the house.” (P20, Rural) Q36: “When my child went out to play with friends, people said “Hey, her daddy and mommy work at the hospital, daddy and mommy has Covid” (P14, Rural) |

| Anticipated stigma | |||

| Fear of being stigmatized while on duty and out of duty | C | Communities | Q37: “At first it was scary when I was just asked to work in the COVID unit. I was a bit scared because I still came home. So, I was like, wow, what would happen. I fear the neighbours.” (P2, Urban) Q38: “People are distributed to do work from home and some work from the office. That was to save a nurse. Instead of being kicked out of the boarding house, that's even more dangerous.” (P23, Urban) Q39: “There is fear, anxiety, fear of being isolated, what will happen to my child. (P14, Rural) Q40: “We will definitely be reprimanded. It might be something like, “You work here, right? That's a COVID place, right? Why do you take public transportation?”. If I took public transportation, it would be like that. “You could infect it, you know. Then I'll catch it, you know.” That's what most people think.” (P15, Urban) |

| Fear of receiving stigma due to seeking psychological support | MH | Colleagues and other officers in the workplace | Q41: “In my own hospital, if someone goes to a psychiatrist, it means that the person is considered mentally unwell. So, that person will be cornered.” (P1, Urban) |

| Internalized stigma | |||

| Viewing self as a carrier of the COVID-19 virus | C | Personal self | Q42: “Yes. Anxious. Afraid. “Am I infected or what?”. I was so scared and panicked that I became a carrier of the virus for my family. They did not distance themselves from me, instead I kept my distance from my family.” (P10, Urban) Q43: “I have children aged 3 years and 4 years, who from the start I had Covid, they have been evacuated. So, we just meet at least once a month, maybe even 2 months. Sometimes I just say hello at the door when I'm delivering something, even though we're both negative.” |

| Having a low impression of self and job | NP | Personal self | Q44: “When it was crowded at that time, I had thoughts like, why did I become a nurse? […] Why do I feel like I'm in the lowest position and being looked down on? […] I was tired and wanted to leave, but I couldn't.” (P21, Rural) Q45: “I felt like they didn't want to be friends with me. I thought I was being ostracized. No one wants to be friends with me.” (P14, Rural) |

| Feeling like the constant object of attention | C | Personal self | Q46: “I feel like people are staring at me when I'm on the street, and it makes me uneasy. […] people look at me like it's a sign that I work in the hospital.” (P2, Urban) |

| Allowing discriminatory treatment of others | C | Personal self | Q47: “Even after a month of isolation, it continued. […] I noticed that my friends were still afraid of me. So finally, in that room, we separated places to put our food and bags. ” (P28, Rural) |

3.5. Enacted Stigma

3.5.1. Physical Avoidance

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many participants found themselves being actively avoided in situations where physical proximity to others was possible. This avoidance was typically expressed through non-verbal cues and was observed across various groups, including the community, family members or relatives, and fellow healthcare workers at health facilities.

In the community, some individuals kept their distance from participants while shopping, whether at small stalls (known as “warung” in Indonesia) or at larger marketplaces (Q1). There was also a noticeable hesitation in accepting money directly from participants during transactions or being near them (Q2).

Additionally, some people would close their homes or residential areas when participants arrived for field assignments. In their neighborhoods, some neighbors avoided visiting participants' homes, refrained from passing in front of their houses, and took steps to minimize contact. These steps included quickly covering their mouths, running away when the participant approached, or even shutting their doors as the participant passed by (Q3).

Some participants also noted that family members and relatives kept their distance (Q4). This behavior manifested in various ways, such as family members talking only at the door, limiting how often they met with the participants, or outright refusing to have them visit. One participant mentioned that his family completely distanced themselves from him when he fell ill with COVID-19, contrasting with how they treated other family members who contracted the virus (Q5).

Some colleagues and other staff at the workplace were also reluctant to exchange greetings with participants, preferring remote communication instead. Some would deliberately choose seats that were far apart, declined invitations to group gatherings, or opted to stay in their dorm rooms to avoid potential encounters with participants. Additionally, some coworkers purposefully distanced themselves when participants were passing by or traveling within the hospital for work-related matters. They might abruptly distance themselves, quickly put on a mask, or avoid face-to-face interactions when the participant approached (Q6).

In other situations, coworkers displayed hesitation when engaging in certain work processes that could lead to close physical proximity with participants. For example, a colleague expressed reluctance to coordinate closely with participants, maintaining physical distance while communicating with them during work-related tasks (Q7).

They also exhibited reluctance when handling reports that participants had touched, displaying wary or disgusted gestures while receiving them. This might involve accepting reports with only their fingertips or asking that the reports be photographed instead of physically handed over. Some colleagues refused to deliver prescribed drugs to participants, instead instructing them to pick up the medication themselves from a designated location. Others prohibited participants from entering the pharmacy area (Q8).

3.5.2. Limited Personal Space and Autonomy

Participants also encountered restrictions and arrangements that infringed on their personal space and autonomy. These actions occurred at various levels, including within families and communities, as well as in healthcare facilities.

One participant mentioned that her family separated her bedroom from the rest of the household and segregated her food, despite not having a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis (Q9). In other instances, families asked participants to resign from their jobs to avoid potential exposure to the virus.

In the community, participants were excluded from gatherings, with some local residents asking them to either return to their rented residences immediately or refrain from leaving home except for work-related reasons. Additionally, some participants experienced a type of “local lockdown” that applied specifically to their houses within their neighborhoods. For example, when one participant tested positive for COVID-19, the area in front of their house was cordoned off, preventing neighbors from passing through (Q10).

In the healthcare setting, participants faced similar restrictions. They were not allowed to leave their designated on-duty residences, except to go to health facilities (Q11).

3.5.3. Suspicious Behavior

During the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses faced behaviors that reflected suspicion. In the healthcare setting, some clients requested that nurses undergo a COVID-19 test before attending to them, asked nurses not to classify them as COVID-19 positive, or inquired if the nurses responsible for their care were also treating COVID-19 patients (Q12).

Some participants also noticed other staff meticulously cleaning areas or objects they had touched or passed by, even though they had recovered from COVID-19 or were not currently infected with the virus (Q13).

At the community level, suspicion and distrust became apparent during field assignments or home visits related to COVID-19 or other health-related activities (Q14). Some individuals even resorted to threats, indicating they would harm the nurses if they contracted COVID-19 during a home visit.

Nurses also encountered suspicion within their own family circles and among their friends. This was often reflected in stringent measures designed to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission. For instance, when nurses wanted to return home, their family members imposed various requirements, such as providing a negative PCR test result and undergoing a 14-day self-isolation period. Before meeting friends, some nurses experienced constant scrutiny, with friends asking if they had taken a COVID-19 swab test before the meeting (Q15).

3.5.4. Rejection

Rejection was a recurring issue for members of the community. For instance, when visiting the field, some individuals directly asked the participants to leave (Q16).

While staying in the area, participants encountered resistance from property owners, who requested that they move out, regardless of whether they had tested positive for COVID-19. Additionally, some participants faced repeated refusals from drivers on ride-hailing apps when they tried to arrange transportation to or from healthcare facilities (Q17).

One participant mentioned that her religious community was reluctant to worship with her because she worked as a nurse (Q18).

3.5.5. Accusing and Demeaning Words

3.5.5.1. Nurses are Seeking Financial Gain from COVID-19

Many participants experienced a sentiment among the public that healthcare workers were exploiting the COVID-19 crisis for financial gain. While providing care to patients, some participants were met with accusations that they had fabricated positive COVID-19 test results, with claims that these results were manipulated for profit. In some cases, people even alleged that participants had falsified results when a patient’s condition deteriorated or they passed away, suggesting that healthcare workers benefited financially from the tragedy (Q19-20). These accusations often came with aggressive language, finger-pointing, or threats, including intentions to harm participants or damage property. Similar sentiments were echoed on social media, where some users claimed that medical professionals received substantial financial incentives from the government when patients died from COVID-19 (Q21). Others went as far as urging the public not to trust healthcare workers or to avoid seeking treatment at medical facilities, fearing they might be falsely diagnosed with COVID-19.

3.5.5.2. Nurses are bringing the COVID-19 Virus

In the workplace, participants working in high-risk areas like emergency rooms or other designated zones within healthcare facilities were perceived as having a heightened risk of transmitting COVID-19 (Q22). Participants returning home often faced ridicule for bringing the virus into their households or causing family members to fall ill. One participant was accused of being the source of infection for a family member who contracted COVID-19 (Q23). Another participant received advice not to reside in the same household as her family members (Q24).

3.5.5.3. Nurses are not Caring and Competent

Participants also endured harsh insults related to their professional competence while caring for clients. Patients and their family members would insult participants, labeling them as incompetent, malevolent, lacking a moral compass, unfaithful to their nursing oath, and worthless when they were dissatisfied with the services provided. One participant even shared that her nursing profession was belittled as a low-income occupation prone to accepting bribes from clients. Negative commentary about nurses' dedication to patient care was also prevalent on social media, with many perceiving nurses as neglectful in handling COVID-19 patients (Q25).

3.5.5.4. Derogatory Nicknames

In the field, participants were sometimes subjected to mockery through derogatory nicknames. For instance, some people shouted “Pocong” (a local ghost figure wrapped in a shroud) at participants when they were seen wearing special outerwear while carrying out their COVID-19 duties in the community; others said that nurses were “cry-babies” when they showed anxiety or negative emotions due to pandemic. Within the family context, one participant mentioned that family members had called them “aunt corona” as a form of teasing or mockery (Q26-28).

3.5.6. Unusual Stare

Participants have also encountered unusual stares from colleagues within the hospital and the community, both while on duty and off duty (Q29). Within the healthcare setting, for instance, when a fellow staff member averted their look to the participant upon her accidental sneeze or cough. Additionally, participants acknowledged that they received unusual stares (such as repeatedly seeing them from head to toe) from community members. This would occur when participants were boarding the bus near the hospital where they worked, when they happened to cough or sneeze while using public transportation, when roaming nearby hospitals, or when dressed in their official attire.

3.5.7. An Exclamation that Felt Isolating

Another form of enacted stigma was an invitation to stay away from distrust or maintain alertness for nurses.

In the community, participants mentioned there was an invitation not to trust them because they were looking for profit or not to be at a close distance from them so they would not get infected (Q30).

A call that felt ostracized has also emerged in the workplace. For example, when co-workers from non-COVID-19 risk zones asked other employees to stay away from nurses who work in the COVID-19 risk zones or those who have worked there. A participant stated that this invitation also occurred even though the participants had recovered because they were considered to still have the potential to be infected with the COVID-19 virus (Q31).

The disturbing appeal not only came as a mouth-to-mouth invitation, but also felt from hospital policy. A participant shared that an open announcement of the prohibition of a meeting between health workers in the COVID-19 risk zones and non-COVID-19 risk zones, unless in a state of “hygiene”, was felt to be stigmatizing (Q32).

3.5.8. Unequal Treatment Compared to Doctors

Another form of enacted stigma was shown in the client’s unequal treatment compared to other health workers. Participants said that clients they cared for valued interactions with doctors more than participants who were nurses. Significantly, clients were also seen as more accepting and appreciative of doctors' messages than participants’ messages. Participants experienced that negative statements were easier to convey to them than to doctors (Q33).

3.5.9. Unfair Treatment Towards Family Members of Nurses

Family members of the participants were often said to receive different treatments. Some participants shared that their neighbors avoided their family members. Some participants' spouses were also shunned in their workplace (e.g., in an office or rice field) or were turned away at shopping places when they wanted to buy necessities (Q34-35). The children in the neighborhood also avoided participant’s children to play (Q36). This treatment occurred even when their family members were not diagnosed with COVID-19.

3.6. Anticipated Stigma

3.6.1. Fear of being Stigmatized while on Duty and Out of Duty

Participants often worried about experiencing various stigmatizing reactions such as being reprimanded, rejected, expelled, made the object of gossip, avoided, or ostracized by society. This anticipatory form then caused some participants' reluctance to carry out their duties and functions optimally as nurses, chose not to go home or hid their positive COVID-19 status.

The fear of being stigmatized by the surrounding environment included fear of being shunned when meeting neighbors (Q37), the topic of gossip in the neighborhood, being kicked out or asked to leave by the landlord (Q38), or having their children ostracized by the community (Q39).

Participants also worried about being reprimanded and rejected in worship meetings or in public transportation if other people determine that they are nurses (Q40).

3.6.2. Fear of Receiving Stigma due to Seeking Psychological Support

For participants who sought mental health support, accessing psychological support in their workplace was not an option, due to the fear of being considered as having a mental health disorder by colleagues in the hospital. Participants were afraid they would be cornered or gossiped about while doing so since privacy issues were easily spread in the health facilities where they worked (Q41). This encouraged participants to use mental health services outside the hospital.

3.7. Internalized Stigma

3.7.1. Viewing Self as a Carrier of the COVID-19 Virus

A significant number of participants saw themselves as carriers of the COVID-19 virus due to their work. This perception persisted even after some had recovered from COVID-19. As a result, participants often took extreme precautions to avoid spreading the virus to others. For example, some refused to meet with friends or family (Q42), while others implemented strict procedures before seeing their loved ones. These precautions could include taking a PCR test, self-quarantining for two weeks, evacuating children to another household (Q43), or adhering to strict health protocols when returning home. Some participants chose to remain indoors for extended periods to minimize the risk of spreading the virus. At work, participants also kept their distance from colleagues, even while wearing full Personal Protective Equipment (PPE).

3.7.2. Having a Low Impression of Self and Job

During the pandemic, several participants reported feeling a diminished sense of self-worth and dissatisfaction with their roles. They often felt stereotyped as “helpers,” particularly when patients asked them to assist with basic tasks like eating or drinking or when clients suggested that they should provide optimal service because they had received financial incentives. Some participants felt inadequate, perceiving themselves as “incompetent,” “not smart,” or “useless” when they were unable to perform specific critical tasks that were outside their scope, such as explaining examination results.

Additionally, some participants felt disrespected and overshadowed by doctors, as clients seemed to place greater trust in and give more respect to doctors' opinions over those of nurses. This sense of inferiority caused some participants to regret choosing a career in nursing. In one instance, a participant considered quitting their job, feeling that nurses were undervalued and treated with disdain. The thought of resigning became more frequent among those working in COVID-19-designated areas, where they felt particularly underappreciated (Q44).

At the societal level, some participants felt that they had no friends due to experiences of being avoided, shunned, and ostracized by others (Q45).

3.7.3. Feeling like the Constant Object of Attention in Public Places

Some participants shared that they felt constantly watched by others in public places because they wore hospital-related attire or took transportation from the health facility where they worked. For example, one participant felt that people were always staring at them while walking home, so they chose to take a detour (Q46).

3.7.4. Allowing Discriminatory Treatment of Others

Some participants felt that it was acceptable for others to discriminate against them and even justified such behavior. For example, they accepted being alienated due to their perceived risk of carrying the COVID-19 virus. They considered stigmatization when they contracted COVID-19 as normal. Furthermore, they compensated for unfair treatment after recovering from COVID-19, such as having their personal belongings separated at work (Q47).

4. DISCUSSION

During an extraordinary event such as a pandemic, stigma could affect almost all nurses, regardless of where they live, whether they are urban or rural, contracted with COVID-19 or have recovered from COVID-19, serving COVID-19 patients or not, in hospitals and in non-hospital facilities. These findings added more knowledge to the findings of studies conducted in Indonesia, which described stigma experiences only from nurses who handled COVID-19 patients in the hospital setting [13, 15, 19]. As also revealed in other studies, during a pandemic, health workers in the community also felt stigmatized [21, 36]. Although, according to a study, the intensity of those in the primary health centre, clinic, or laboratory was not as much as hospital nurses [21], this group also requires attention that is no less important.

This study showed stigma impacting those who are part of a group with similar attributes, associated with outbreak handling. Whether these people work in direct handling of the disease at focus or not, the group attributes they hold may provide a form of reference to ‘marks’ that are not expected, unwanted, or disliked in their societal context [37]. This study indicated that the shared attributes or ‘marks’ that foster stigma to nurses could be, first, the perceived risk that nurses could pose a COVID-19 threat to society and, second, the shared disliked characteristics that people particularly attach to the nurses as a group. This suggests that during COVID-19, stigma towards Indonesian nurses is not only related to COVID-19 risk but also intersects with the nursing profession.

There were twelve perpetrators identified as sources of stigma to Indonesian nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. The types varied from nurses themselves, friends and family at the interpersonal level, different types of communities; colleagues and other officers in the workplace up to the institution policy. Consistent with the findings, some of these sources of stigma have been noted as well in other studies conducted in Indonesia as the source of stigma for nurses who work in pandemic situations.

Similar to other studies, stigma could come from friends [16, 21] and community members [12, 13, 15, 21, 36]. Studies often did not clearly address the type of communities [12, 16], apart from neighbors [13, 19], the owner of the rented house and transport drivers [19]. This study added five more types of communities that perpetuated stigma. This study identified additional sources of stigma, including communities near nurses' workplaces, those visited during fieldwork, religious congregations, shopping areas, and online platforms (netizens).

Stigma can also originate from nurses' family members, an aspect that has been scarcely explored in studies on Indonesian nurses. Apart from the current study, only one other study has examined family members as a source of stigma [13]. In the literature, family members of nurses were often pictured as both affected by stigma [13, 16, 19] and as sources of support for resilience against stigma [15, 16, 18, 19]. This study similarly found that nurses' families experienced stigma, but it also revealed that avoidance and suspicion may originate from both nuclear and extended family members. In the previous epidemic situations (i.e., Ebola), stigmatization from family members caused increased stress for nurses [22].

Furthermore, stigma from colleagues, including those in non-COVID wards and other workplace staff, as documented in literature [15, 16, 19, 26] was also observed. This study identified two additional groups perpetuating stigma towards nurses in the workplace, a rarity in Indonesian research. Firstly, the healthcare recipients, consisting both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients and family. Secondly, structural stigma manifested in institutional policies during the pandemic, such as regulations that blatantly told healthcare workers in Covid and non-Covid units to stay away from each other, was felt discriminated by some nurses.

When examining the manifestations, most of the time, extreme actions such as rejection and expulsion were mainly reported in other studies [19, 20, 38, 39]. However, this study emphasizes that manifestations of experienced stigma are not confined to extreme behaviors only, which typically draw immediate attention. Stigma can manifest in various everyday events and in settings crucial to nurses, significantly impacting their wellbeing and the ability to perform duties. This study shows that physical avoidance occurred in nurses’ home, their neighborhoods, workplaces and shopping areas. Nurses’ families were also affected. While the literature has acknowledged the avoidance of nurses' family members, typically linked to neighborhood stigma [13], this study reveals that the impact can extend beyond their neighborhood to workplaces and shopping places as well. This suggests that the pandemic situation may promote family stigma, which in turn negatively impacts the quality of life of nurses’ families [40].

In addition to being shunned, nurses also experienced restrictions on their personal space and autonomy, even when they were not infected or were COVID-19 survivors. For example, their personal belongings were separated in the workspace. A study also revealed similar treatment, where nurses' cars or ATMs were reluctant to be touched by others [9]. This depicts that objects owned by nurses could be assumed to be an integral part and extension of themselves as a “risk group” [9].

Nurses also received labels and mocks on their identity as a person and a nurse. Nurses were labelled as carriers of the COVID-19 virus, as noted in another study [26]. This label could expand to nurse’ family [13, 16, 19]. In addition, nurses were accused, either individually or collectively, of falsifying positive COVID-19 test results to receive financial benefits. And, some nurses frequently experienced demeaning words about their profession that addressed them as a useless, unprofessional, a profession of low income, and easily bribed. These forms of stigma are still seldomly addressed in existing stigma-related studies conducted in Indonesia.

Behavior that signalled suspicion from non-COVID patients or families during bedside interactions also occurred. Nurses from non-COVID wards were questioned about their involvement with COVID patients, with some even warning them to avoid transmitting the virus. This again highlights that all nurses, regardless of their role in managing the pandemic, face stigma and its burdens. Further investigation into the comparative burden between nurses involved in pandemic care and those who are not could be explored in future studies.

Furthermore, the policy mandating workplace distancing, although it sounded valid for prevention, could be perceived as isolating or discriminating against nurses, showcasing structural stigma during the pandemic [41]. This issue is still scarce to be discussed in literature even though this potentially could harm the affected group [42]. Manifestations of structural stigma that affects nurses’, the consequences, and how to best formulate a policy that will not add to stigma formation in the pandemic can be explored. Studying topics in the newspaper released during the pandemic could be a starting point to learn more about this [43].

From the anticipated stigma perspective, this study emphasized that nurses expressed concerns about potential stigmatizing behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as fear of avoidance, gossip, reprimand, or rejection in or outside the workplace. Critical to discuss from this study is that anticipated stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic extends beyond fears related solely to the threat of the virus. It also encompasses concerns about stigmatizing behaviors associated with mental health issues. Some nurses in this study expressed reluctance about accessing mental health support available in their workplaces due to perceived workplace gossip that could tarnish their image. This highlights that stigma surrounding mental health problems still exists, even among healthcare workers or those employed in health institutions. This demonstrates that advancements in addressing mental health issues have not been matched by reductions in the stigma associated with such problems [44]. Many studies mentioned that the pandemic has brought in itself a higher mental health crisis among nurses [45]. Thus, mental health support is important during this time. Stigma on mental health issues would cost nurses more, as it could hinder them from seeking mental health assistance [46, 47]. These findings are vital due to their crucial impact on mental health [48] and considering the high level of perceived stigma among nurses observed in Indonesia during the pandemic [14, 49].

In terms of internalized stigma, nurses seeing themselves as carriers of the virus was a commonly reported form, although not explicitly labeled as self-stigma in previous literature [9, 13, 15, 21, 50]. In a pandemic situation, nurses often believe that they could endanger others even if they are not infected [9, 13, 15, 21, 50]. They often have “the feeling of being infected and dirty” [51]. Following the conceptualisation of internalized stigma, these maladaptive beliefs can be self-deprecating [52, 53]. This is shown in a nurse who accepted unfair treatment and rationalized stigmatizing behaviors in this study. Other forms of internalized stigma include feeling like a constant object of attention in public places. Simeone et al. described this as “gun-sight look,” where nurses perceive themselves as the center of attention in the context of pandemic [9]. The label “doctor’s helper” was also often internalized and found to burden nurses during the pandemic, as evidenced in this study.

This study found that Indonesian nurses experienced various forms of stigma in the pandemic trajectory. These experiences ranged from stigma associated with the COVID-19 threat to those stemming from negative perceptions of the nursing profession, including stigmatization related to mental health issues. The fact that stigma intersected with other conditions beyond COVID-19 threat indicates a serious concern that must be made. Hence, tackling stigma toward nurses in future health crises should not solely focus on disease-related concerns such as fatality or transmissibility. It is essential to address the underlying factors contributing to the negative perceptions of nurses. Tackling stigma related to the identity of a group may need a lot of work and time as it may intersect with multiple drivers that shape it, especially in Indonesian society which is lacking the knowledge about nurse roles and still difficult to capture their positive images [54]. Other things that are also critical are efforts to develop constructive beliefs or replace the dysfunctional beliefs around the disease at focus in the pandemic and tackling mental health-related stigma. Nurses were found to be at a higher risk of experiencing stigma during the pandemic compared to doctors [20]. Thus, every effort is essential in lowering their burden in such unexpected times.

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study adds to the scarce literature on stigma in Indonesia, addressing gaps in recent research by including a diverse group of participants and offering a comprehensive understanding of stigma sources across various settings. The findings also highlight the need for further research to explore the impact of intersecting conditions on disease-related stigma among nurses during pandemics. Some limitations of this study include the use of online channels for participant interaction, potentially limiting rapport building during interviews. However, opening questions which facilitated more casual discussions had been done to mitigate this issue. Another concern is the transferability of findings, which may be restricted to Indonesia or areas with similar socio-demographic backgrounds. Nevertheless, this could still be challenged, as stigma is closely tied to the specific sociocultural sides in a region.

CONCLUSION

The burden of stigma on Indonesian nurses during the pandemic is significant, encompassing enacted, perceived, and internalized stigma. It is also linked to the pandemic threat, societal perceptions of nurses, and stigma around mental health. This highlights a triple burden for nurses. Stigma was felt across various settings, regardless of nurses’ roles or involvement in the COVID-19 response. This stigma extends to their families, affecting them in everyday places like neighborhoods, markets, and workplaces. Sources of stigma include individuals, communities, and structural factors, with families sometimes both affected and responsible.

This study emphasizes the need for future pandemic preparedness efforts to address stigma comprehensively, considering not only the disease threat but also societal perceptions of nurses and mental health issues. Anti-stigma programs should cover all nurse types and associated groups, requiring long-term strategies aligned with local perspectives.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CAQDAS | = Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software |

| PPE | = Personal Protective Equipment |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study obtained ethical clearance from the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of Krida Wacana Christian University (Reference number: 1090/SLKE-IM/UKKW/FKIK/KE/VII/2021).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.