All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Relationship between Health Professional Involvement, Organizational Factors, and Professional Outcomes

Abstract

Introduction

The rapidly growing challenges of healthcare systems require a healthcare environment that can create symbiotic interactions between workers and their work. In this study, we analyzed the relationship between professional involvement, organizational factors, and professional outcomes in a teaching hospital in Morocco.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study of nurses and physicians at Ibn Rochd Teaching Hospital using a structured questionnaire. Data were described using frequencies and percentages. Spearman’s rank-order correlation test was used to evaluate correlations between items.

Results

We found positive linear associations between professional involvement items and both organizational items and professional involvement items. These associations highlight the possibility of interactions between health professionals’ commitment, healthcare settings, and outcomes (mental well-being, turnover, and job satisfaction).

Discussion

These findings contribute to a growing body of literature emphasizing the interconnectedness of individual and organizational factors in healthcare settings. By examining these relationships within a Moroccan context, this study offers valuable insights into the unique challenges and opportunities faced by healthcare workers in African settings, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive interventions.

Conclusion

Decision-makers should develop or improve policies that consider interactions between organizational factors and worker well-being and engagement. In addition, comparative studies that include all relevant stakeholders should be conducted.

1. INTRODUCTION

The global workforce in 2020 included 12.7 million physicians, 3.7 million pharmacists, 2.5 million dental practitioners, 29.1 million nurses, and 2.2 million midwives [1]. The density of health workers varied considerably among countries, with high-income and low-income countries having densities that differed by a factor of 6.5. By 2030, the total health workforce is projected to reach 84 million [1].

The growing challenges facing health systems require a care setting that supports symbiotic relationships between work and workers. Nurses account for the highest proportion of the global health workers, estimated at 27.9 million practitioners [1]. Morocco has 13.91 nurses and midwives per 10,000 population. These figures highlight the importance of nurses' involvement in healthcare provision and the need to investigate factors influencing their health and work commitment. Involving the right stakeholders from the beginning improves the accuracy, stability, and implementation of health service planning. This is the case at all subnational, national, and regional health system levels, and at all system capacities or resource levels [1].

An organization is a coordinated group of individuals who carry out tasks to accomplish a common purpose or set of goals [2]. A resource common to all organizations is people (human resources). The interactions between individuals, groups, and their organization and environment, based on a set of fundamental beliefs, are collectively known as organizational culture. Individual behaviors and expectations are shaped by the relationships between individuals and groups inside organizations; some people must take on leadership positions, while others assume the duties of followers [2]. Organizational culture is highly valued by healthcare organizations because it involves shared perceptions and methods of approaching work [3]. As psychological illness can be linked to 17 to 33 percent of absenteeism, organizational culture can significantly impact employee well-being, mental health, and the working environment [4]. Organizational culture and management or leadership style are often considered interlinked, with the leadership both shaping and shaped by culture [5]. Studies conducted in the last 10 years have consistently demonstrated a connection between managerial attitudes and staff well-being [6]. Poor leadership can be associated with up to 75 percent of the inappropriate behavior of healthcare workers toward patients [7].

The degrees of personal engagement and self-investment in work can be considered key indicators of engagement from a psychological perspective [8]. Engagement is a psychological state related to work that encompasses vigor, involvement, and cooperation, as well as behaviors that serve organizational goals [9]. It has been reported that engaged staff have fewer psychological problems at work than non-engaged staff [10]. In addition, healthcare workers’ intention to leave their jobs is inversely associated with their level of professional involvement. This has major implications for healthcare organizations, as the Global Strategy for Human Resources for Health projects a global shortage of 18 million health workers by 2030 [1].

“Outcomes” (professional or work outcomes) can be defined as states or conditions that emerge from work and are critical indicators of performance [11]. These include burnout, job satisfaction, quality of care, and turnover intention [12]. Turnover intention refers to an employee’s willingness to leave an organization due to dissatisfaction and seek other job opportunities [13]. Generally, before making such a decision, the worker passes through a phase of reflection [14]. Turnover rates vary across countries, reaching 44 percent in New Zealand, 27 percent in the US, 20 percent in Canada, and 15 percent in Australia [15]. The turnover cost per person was $48,790 in Australia (50 percent of indirect costs were related to termination, and 90 percent of direct costs were due to temporary replacement costs), compared with $20,561 in the US, $26,652 in Canada, and $23,711 in New Zealand [15]. Turnover rates can be reduced by job satisfaction-pleasurable or positive emotional states experienced by employees at work-which can also improve worker performance and psychological well-being, as well as reduce absenteeism [16].

The relationship between workplace organization (or management style) and workers’ commitment and professional outcomes has been extensively studied [17]. It was found that organizational culture has a direct and significant positive influence on worker commitment and performance, while Guerrero et al. reported that increased worker commitment reduces workers’ anxiety and stress symptoms but increases their turnover intentions [18]. Pedrosa et al. concluded that the turnover rate in healthcare settings can be decreased by addressing factors related to organizational culture and leadership [19]. Labrague et al. noted positive relationships between perceived organizational politics and job stress, turnover intention, and job burnout, as well as a negative relationship between perceived organizational politics and job satisfaction. Greater employee engagement and job satisfaction are related to a positive organizational culture, characterized by strong leadership in a supportive work setting [20]. In contrast, they are negatively linked to negative cultures like hierarchical environments [21]. Finally, De Simone et al. found a correlation between job satisfaction and engagement, self-efficacy, and capacity among workers, as well as a negative correlation between job satisfaction and turnover [22].

Despite the extensive literature on work organization, health worker commitment, and job outcomes, studies based in African countries, such as Morocco, are scarce. This study addresses this gap by describing health workers’ involvement and perceived organizational and professional outcomes, and by analyzing the correlations between professional involvement and these outcomes among health workers at a Moroccan hospital.

2. METHOD

2.1. Study Setting, Design, and Population

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Ibn Rochd University Hospital Center, Casablanca, between November 2024 and February 2025. This teaching hospital has 1,685 beds and 3,896 staff. It comprises Ibn Rochd Hospital (1,020 beds), Abderrahim Harouchi Mother-Child Hospital (374 beds), August 20, 1953 Hospital (291 beds), a consultation center, and a dental care center. The sample consisted of all full-time and part-time physicians and nurses who had worked in the psychiatry, traumatology, neurology, intensive care, urology, cardiology, addictology, endocrinology, nephrology, oncology, pneumology, or radiology unit for at least a month. External personnel, such as trainee physicians, nursing students, and staff who were absent during the study period, were excluded.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.1.2. Work Unit

Work in one of the following units: psychiatry, traumatology, neurology, intensive care, urology, cardiology, addictology, endocrinology, nephrology, oncology, pneumology, or radiology. These units were selected to capture a range of experiences in different medical specialties and care settings.

2.2. Sampling

The sample size was determined using the single population proportion formula

, assuming an expected burnout prevalence of 50 percent among health workers based on a previous survey conducted in Morocco [23], with a 95 percent confidence level and a 5 percent margin of error. The sample size calculated using these assumptions was 384. To select participants in each unit, simple random sampling was conducted using worker lists provided by the human resources department.

, assuming an expected burnout prevalence of 50 percent among health workers based on a previous survey conducted in Morocco [23], with a 95 percent confidence level and a 5 percent margin of error. The sample size calculated using these assumptions was 384. To select participants in each unit, simple random sampling was conducted using worker lists provided by the human resources department.

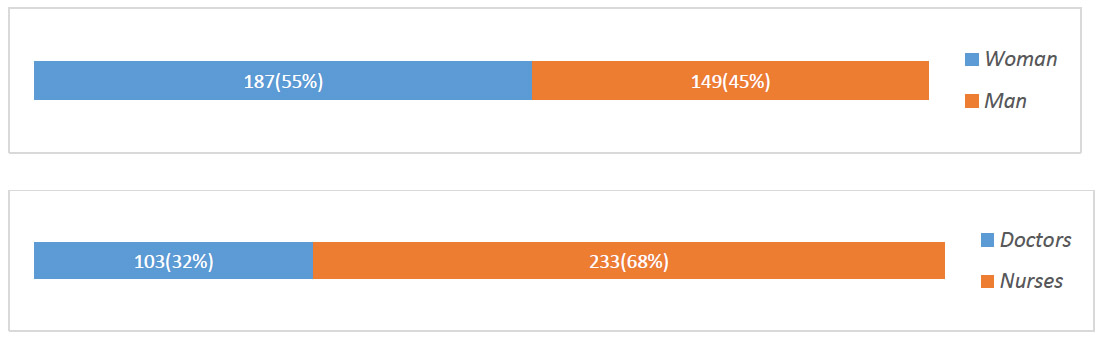

In order to characterize our sample more precisely and examine the potential influence of these variables on the results, we collected data on the age, seniority, and gender of the participants. Age was measured in full years, seniority was measured as years of service at the hospital, and gender was recorded as male or female. The average age of participants was 31 years old, the average seniority was 5 years, and the sample consisted of 55% women and 45% men. The inclusion of these variables will allow us to explore potential differences in terms of professional involvement, perception of organizational culture, and professional outcomes.

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Recruitment

We recruited participants through the heads of care units, who received and shared the survey information with their colleagues. Participants were informed about the study, particularly its aims, data collected, participation procedures, benefits, and risks, and consent was obtained.

2.3.2. Data Collection Tool

The data were collected through a self-administered questionnaire via the Google platform. The questionnaire design was based on the literature, particularly a tool developed and validated by the Committee for Clinical Evaluation and Quality in Aquitaine (CCECQA) in France [24]. The questionnaire consisted of dimensions such as participant characteristics, organizational culture, commitment, and professional outcomes, and it was pretested on 10 physicians and 15 nurses.

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Ibn Rochd University Hospital Center, Casablanca, between November 2024 and February 2025.

2.4. Measurements

Participant characteristics were sex (female or male) and profession (nurse or physician). The questionnaire assessed three main dimensions: professional involvement, organizational culture, and professional outcomes.

Professional involvement comprised items such as professional commitment to the service, acceptance of service standards, and career aspirations. The organizational dimension included several sub-dimensions: management (covering individuals’ positions within teams, discrimination levels, tasks, objectives, organizational learning, frequency of conflicts between professionals, conflict management, and types of behavior encouraged), hierarchical support, and relationships and communication (including interprofessional relationships, departmental coordination, and information sharing). Professional outcomes were measured through items such as job satisfaction, willingness to stay, workload, burnout, and efficiency. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1= strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree), with scores of 4 and 5 regarded as positive responses, 1 and 2 regarded as negative responses, and 3 regarded as a neutral response.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The heads of the teaching hospital and care units approved this study, as well as the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of Casablanca (Ref-n/12/24). Participants gave their informed consent after receiving information about the investigators, the aims of the survey, participation procedures, risks, benefits, confidentiality, anonymity, and data safety.

2.6. Data Analysis

The data were described using frequencies and percentages. We tested the strength of the correlation between organizational factors, staff involvement, and professional outcomes using Spearman’s rank-order correlation coefficient r (|r| < 0.3 = weak; 0.3 < |r| ≤ 0.6 = moderate; |r| ≥ 0.7 = strong). Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05, and analyses were conducted using XLSTAT software.

3. RESULTS

A total of 336 staff members from 12 departments responded to our questionnaire. About 56 percent of respondents were female, and about 68 percent were nurses (Fig. 1).

3.1. Professional Involvement

The proportion of positive responses for items in this dimension varied between 38 and 69 percent, and the proportion of negative responses varied between 23 and 56 percent (Table 1).

| Dimensions and Items | Positive (%) |

Negative (%) |

Neutral (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional involvement | - | - | - |

| Professional commitment to the department | 69.05 | 23.51 | 7.44 |

| Acceptance of department norms | 41.07 | 54.76 | 4.17 |

| Career aspirations | 37.80 | 56.25 | 5.95 |

| Organization | |||

| Department management | - | - | - |

| Taking into account the individual within the collective | 15.18 | 83.33 | 1.49 |

| Discriminatory practices | 32.14 | 63.69 | 4.17 |

| Assigning tasks and objectives | 30.36 | 66.96 | 2.68 |

| Organizational learning | 7.44 | 86.31 | 6.25 |

| Frequency of conflicts between professionals | 10.71 | 81.85 | 7.44 |

| Conflict management | 25.60 | 72.32 | 2.08 |

| Types of behaviour encouraged within the department | 83.04 | 12.50 | 4.46 |

| Relationships and communication within the department | - | - | - |

| Relationship between paramedical professionals | 35.12 | 62.50 | 2.38 |

| Relationship with and between doctors | 45.83 | 48.21 | 5.95 |

| Coordination within the department | 41.37 | 54.17 | 4.46 |

| Distribution of information | 35.12 | 61.90 | 2.98 |

| Department manager support | 23.81 | 71.43 | 4.76 |

| Professional outcomes | - | - | - |

| Job satisfaction | 20.45 | 75.30 | 4.17 |

| Willingness to stay | 26.79 | 71.13 | 2.08 |

| Workload | 19.64 | 76.19 | 4.17 |

| Burnout | 7.44 | 88.99 | 3.57 |

| Perceived department effectiveness | 43.75 | 53.57 | 2.68 |

Sex and profession distribution.

3.2. Organizational Culture

The proportion of professionals having a positive perception of items in this dimension varied between 7 and 83 percent. The proportion of negative responses varied between 12 and 86 percent. Neutral responses ranged between 1 and 7 percent (Table 1).

3.3. Professional Outcomes

The percentage of positive responses to the items in this dimension varied between 7 and 44 percent, and the percentage of negative responses varied between 53 and 89 percent. Between 2 and 4 percent of participants gave neutral responses (Table 1).

Spearman rank-order correlation tests indicated a strong linear relationship between organizational culture items and professional involvement items, particularly between career aspirations and departmental coordination (r = 0.993) and between career aspirations and information sharing (r = 0.995) (Table 2). Strong correlations were also observed between professional involvement items and professional outcome items, such as between acceptance of department norms and perceived department effectiveness (r = 0.997), as well as between job satisfaction and willingness to stay (r = 0.990) (Table 3).

4. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to describe health professionals’ involvement, perceived organizational factors, and professional outcomes and to analyze the relationship between professional involvement, organization, and outcomes. It was found that the proportion of favorable impressions about professional involvement varied between 38 and 69 percent, while between 7 and 83 percent of professionals had a positive vision about the organization. We also observed a link between organizational culture items and professional involvement items, as well as between professional involvement items and professional outcomes. Guerrero et al. showed that good practices and the availability of organizational resources related to patient care can be explained by professional engagement [25], while Jain et al. found that organizations with strong supportive leaders had greater employee involvement [26]. According to Naidoo et al. [27], organizations can increase employee involvement, and Hassan et al. [28] and Bolandian et al. similarly found that organizational factors have a significant positive relationship with employee involvement [29]. Mullins-Jaime showed that safety and environmental management systems significantly impact worker commitment. We also found that coordination within the department, distribution of information, and support from the department manager were correlated with professional commitment [30].

Bakker et al. [31] and Brown et al. reported that burnout and commitment are linked to job-related outcomes [32]. We also found that commitment to department norms is linked to burnout, in line with Tetikcok et al. [33] and Panari et al. [34]. The strong link between professional engagement and burnout observed in our study can be partly explained by the absence of mediators such as professional self-concept and psychological capital [35]. Several studies have also reported that organizations with supportive or transformational management are negatively associated with burnout [36].

The link between employee commitment and job satisfaction observed in this study concurred with previous research [37]. De Simone et al. found that employee commitment affected nurses’ turnover intention, supporting our findings. Specifically, we noted a significant relationship between professionals’ commitment and their intention to stay [22, 38]. Similarly, Narayana et al. revealed an inverse relationship between professionals’ [39] commitment and turnover intention, in line with previous studies [40]. The strong link between professional commitment and turnover can be explained by the large number of newly hired professionals among our participants [41]. It may also be explained by professionals’ personal characteristics, such as their beliefs and work values [42].

Table 2.

| Items | 2E | 2F | 2G | 3A | 3B | 3C | 3D | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | - | - | 0.987* | - | - | - | - | - |

| 1B | 0.736* | 0.902* | - | 0.979* | 0.977* | 0.991* | 0.979* | 0.877* |

| 1C | 0.804* | 0.942* | - | 0.995* | 0.949* | 0.993* | 0.995* | 0.923* |

1A ‐ Professional commitment to the department.

1B - Acceptance of department norms.

1C. Career aspirations.

2E. Low frequency of conflicts between professionals.

2F. Conflict management.

2G. Types of behaviour encouraged within the department.

3A. Relationships between paramedical professionals.

3B. Relationship with and between doctors.

3C. Coordination within the department.

3D. Distribution of information.

5. Department manager support.

| Items | 6A | 6B | 6C | 6D | 6E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | - | 0.091* | - | - | - |

| 1B | 0.847* | 0.912* | 0.838* | 0.737* | 0.997* |

| 1C | 0.898* | 0.951* | 0.891* | 0.804* | 0.982* |

1A ‐ Professional commitment to the department.

1B - Acceptance of department norms.

1C. Career aspirations.

6A. Job satisfaction.

6B. Willingness to stay.

6C. Workload.

6D. Burnout.

6E. Perceived department effectiveness.

Our results suggest that job satisfaction is influenced by several interrelated factors. For example, only 20.45% of participants expressed a positive perception of their job satisfaction, while a significant majority (75.30%) expressed a negative perception, with the remaining participants expressing a neutral view. This low satisfaction seems to be linked to a lack of support from management, as only 23.81% of participants have a positive perception of the support provided by their department manager. Additionally, there is a lack of organizational learning opportunities, with only 7.44% of participants having a positive perception of organizational learning. These observations suggest that department head support and professional development opportunities are crucial factors for job satisfaction among healthcare professionals in our sample.

This observation aligns with the findings of Johansson et al. [43], who demonstrated that transformational leadership and a supportive work environment correlated with greater job satisfaction among nurses. Notably, they also identified strong management support and opportunities for professional growth as key mechanisms for fostering employee value and well-being, ultimately boosting job satisfaction, consistent with our study's findings.

5. RECOMMENDATIONS

The data from this study may be useful for policymakers, healthcare professionals, health worker training institutes, and researchers, as the growing challenges of healthcare systems will require settings that can create symbiotic interactions between workers and their work. Thus, the study’s findings can help policymakers with decision-making and planning. Our results allow health workers to learn about the interactions between their psychological well-being, organizational factors, management style, turnover, and career development. Human resources managers in healthcare settings can use the data to improve worker wellness and productivity. Our results can also help health worker training institutes ensure that training programs account for the interactions between healthcare settings, professionals’ welfare, management style, worker efficacy, and turnover. Finally, they contribute to the literature on professional involvement and organizational culture in healthcare settings, particularly from African perspectives.

5.1. Management Support

Healthcare facilities should implement training programs for department managers to help them develop skills in transformational leadership and effective communication [6].

Healthcare organizations are supposed to invest in psychological support programs to reduce burnout and promote employees' well-being [44]. These programs can include individual or group counseling, stress management and resilience training, and promoting healthy work-life balance activities.

Weigl's research concluded that nurses who felt valued by their management were significantly more work-satisfied [45].

5.2. Learning Opportunities

Organizations need to offer employees continuous professional development opportunities, such as training programs, workshops, conferences, and mentoring schemes [46].

5.3. Communication and Transparency

Organizations need to establish open and transparent channels of communication to allow employees to pass on their concerns, suggestions, and ideas [47].

In order to enhance communication and openness, organizations may consider having regular meetings with management, secret suggestion boxes, and open lines of communication to enable employees to express their views and suggestions.

6. STUDY LIMITATIONS

Although this study is one of the first in Morocco or Africa to address the theme of professional involvement and organizational culture in healthcare settings, data were only obtained from some units of a single teaching hospital, limiting its outcomes. In addition, this study predominantly reflected the perspectives of subordinate staff, as the majority were nurses, and employed a cross-sectional design. Caution is therefore required in the interpretation and generalization of its results.

While we collected detailed quantitative data regarding professional engagement, organizational variables, and outcomes, we did not include direct quotes from participants in our findings. This was to ensure participant confidentiality and anonymity, as the publication of verbatim quotations had the potential to allow their identification. We recognize that the inclusion of direct quotes would have added liveliness to the presentation of our findings, providing more specific and evocative accounts of healthcare professionals' experiences. However, we believe that the quantitative data we have presented, combined with the counterpoint of our findings with the wider literature, provides a sufficient basis for our conclusions.

CONCLUSION

This study analyzed the relationship between health workers’ involvement, organizational factors, and professional outcomes in a hospital in Morocco. Despite the limited generalizability of these results, they can be helpful for decision-makers, healthcare unit managers, healthcare workers, and researchers. In particular, decision-makers should formulate policies that consider the interactions between organizational factors, the psychological and physical well-being of employees, and worker commitment. Academic decision-makers should develop programs and organize training workshops that account for the interactions between healthcare environments, the well-being of healthcare workers, and their careers. Further studies are recommended, particularly comparative studies, to take into account the perspectives of all stakeholders (decision-makers, resource managers, and health workers).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: A.L.: Visualization; M.A.: Validation; A.S.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OT ABBREVIATIONS

| CHU | = Centre Hospitalier Universitaire |

| CCECQA | = Committee for Clinical Evaluation and Quality in Aquitaine |

| XLSTAT | = Statistical Analysis Software for Microsoft Excel |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The heads of the teaching hospital and care units approved this study, as well as the Ethics Committee for Biomedical Research of Casablanca, Morocco (ref-n/12/24).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [A.S] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.